PATELLAR LUXATION

What is Patellar Luxation

Patellar luxation (kneecap dislocation) is a common condition in dogs that can cause pain, lameness and arthritis. The condition typically causes a skipping lameness in small breeds but is now being recognised in large breed dogs, especially Labradors.

Patellar luxation is commonly diagnosed before any clinical signs develop, but early surgical intervention is recommended to try and slow degeneration of the knee cap that causes significant pain and arthritis.

Cardiff Canine Knee Clinic offers expert surgical management of this debilitating disease at affordable, fixed prices.

With over 10 years of orthopaedic experience Tom offers an initial free consultation to allow him to examine your pet, discuss your pet’ s lifestyle, and advise you on how best to manage this disease in your dog.

Cruciate Surgery : TPLO £3500 | Lateral Suture £1750 | Patellar Luxation £2500

[ultimate_exp_section title=”WHAT IS THE PATELLA?” background_color=”#ffffff” bghovercolor=”#ffffff” title_active_bg=”#ffffff” cnt_bg_color=”#ffffff” icon=”Defaults-chevron-down” new_icon=”none” icon_align=”right”]

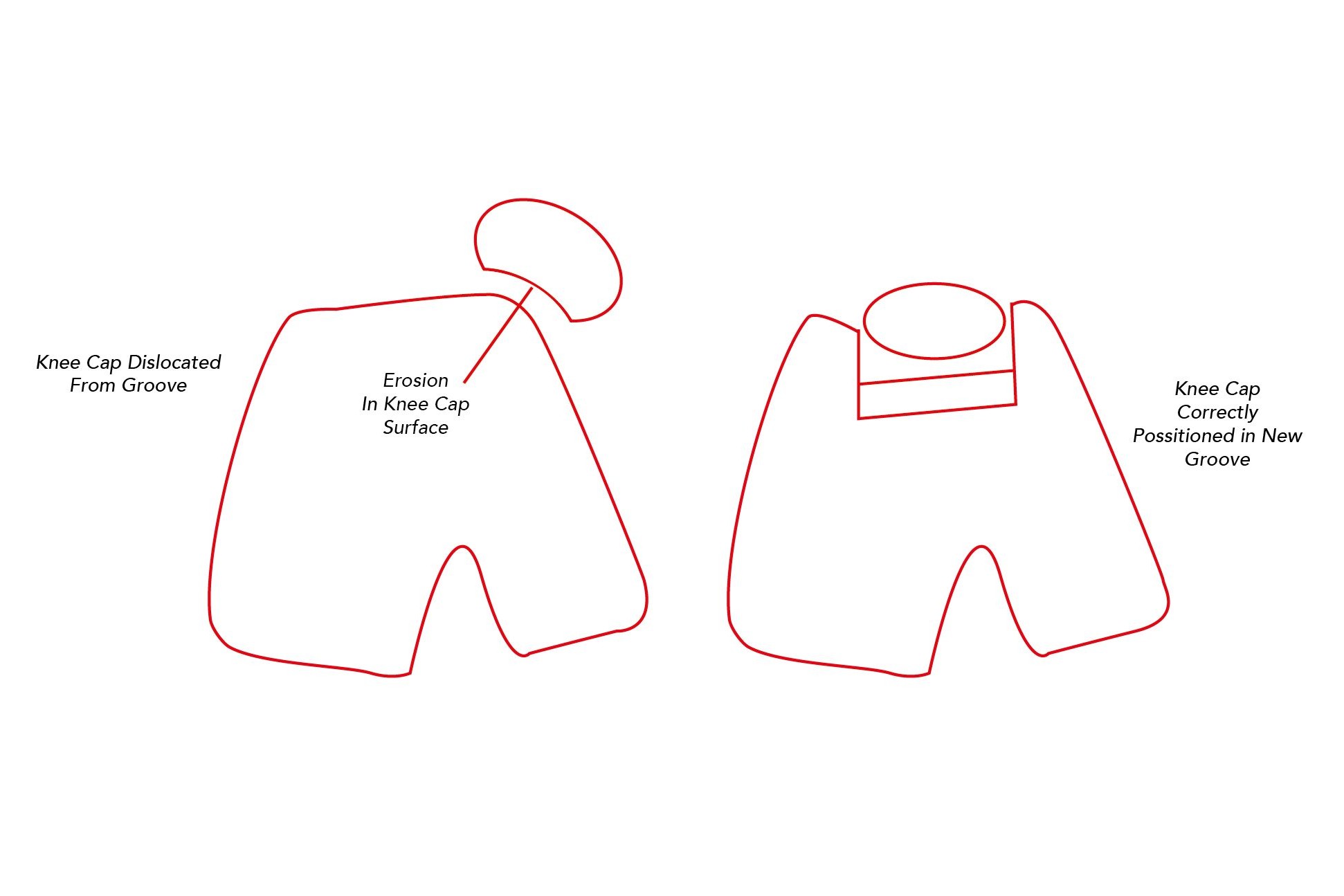

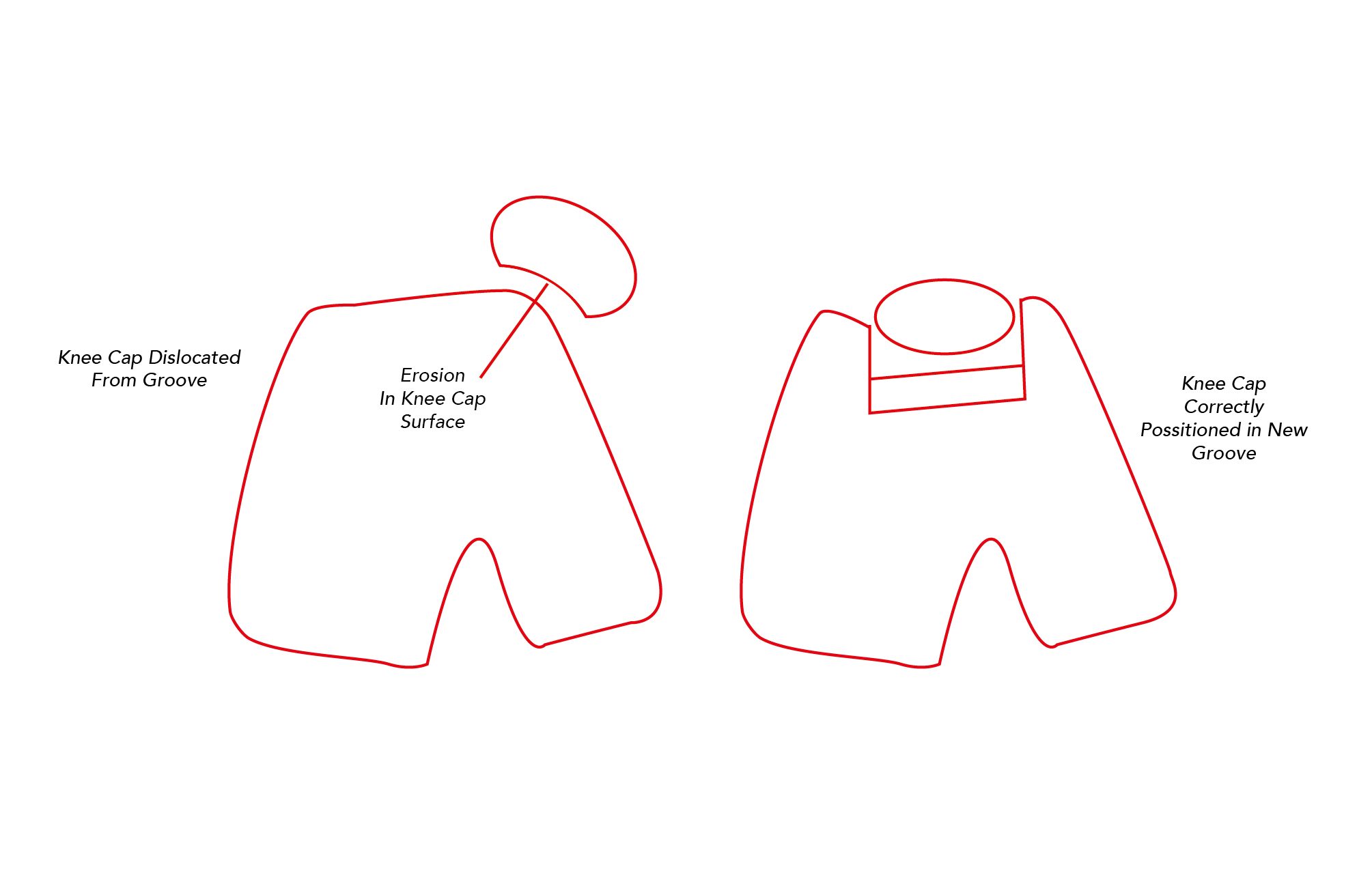

The patella (knee cap) is a thick, circular bone which articulates with the femur (thigh bone) forming part of the knee joint. It covers and protects the front of the knee joint moving up and down a trochlea (groove) in the thigh bone.The knee cap and groove are both covered in cartilage allowing smooth, friction free and pain less movement of the two bones.

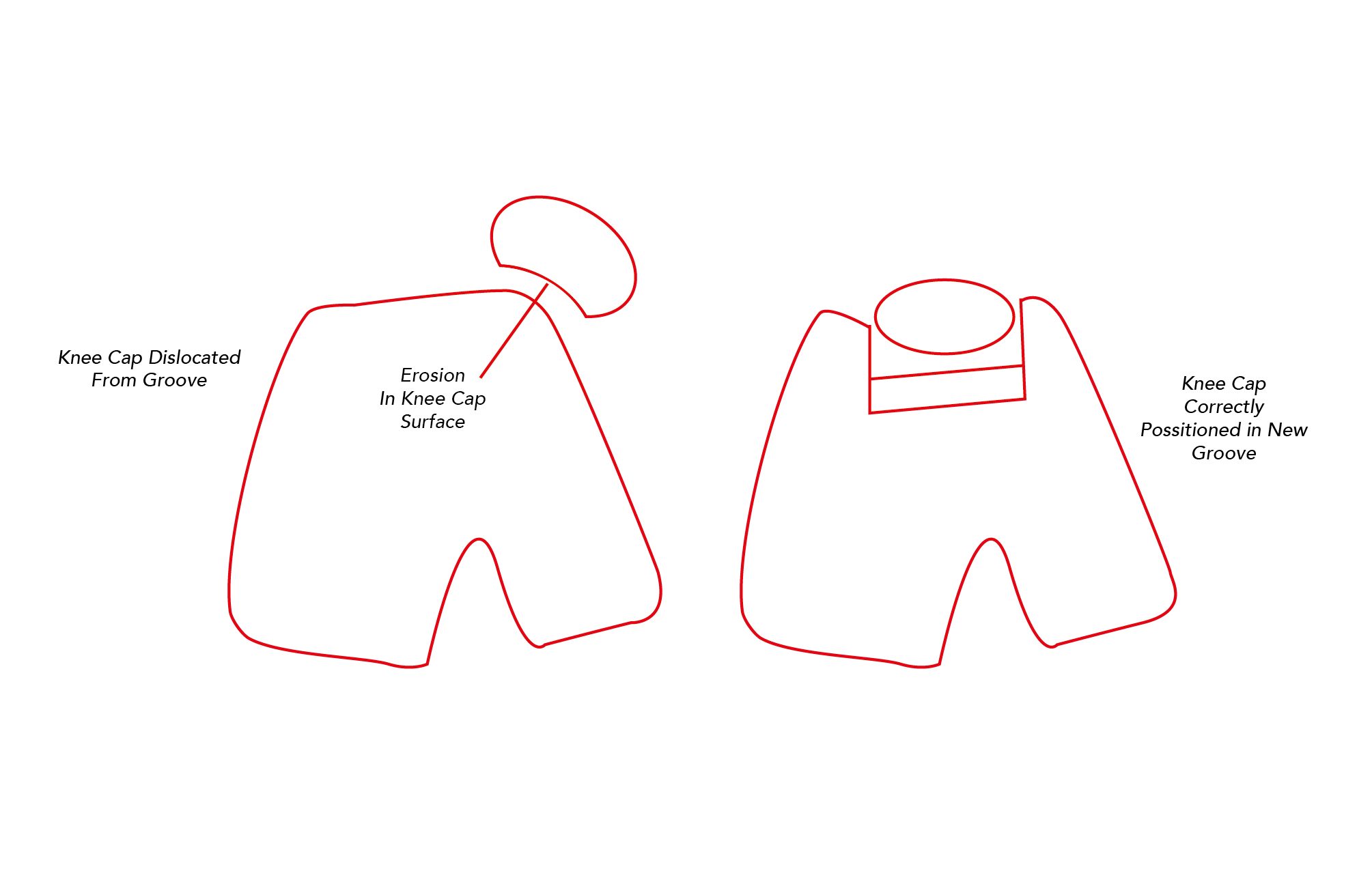

The knee joint is designed so that the knee cap moves within the groove. The cartilage covering the back of the knee cap and groove allows smooth, pain free movement of the two against each other. When the knee cap moves outside of the groove it repositions onto bone and the knee no longer moves in the correct way. This bone acts as an abrasive against the knee cap cartilage grinding it off. The end result of this process is that bone in the knee cap is exposed causing increased inflammation and pain.

Most symptomatic dogs fall in to two different categories

1/ Young dogs who skip – these are often small terrier type dogs that hold their leg up for a few paces before putting it back down. Often they will kick the affected limb out. In these cases the knee cap is dislocating and getting stuck, and as a result they cannot bend their knee joint properly.

2/ Older dogs who have generalised stiffness and lameness. Often their knee caps have always been dislocated and as a result the knee cap has worn away causing severe arthritis. The knee joint can seem markedly thickened and the dog has difficulty climbing stairs, jumping into the car and completing walks.

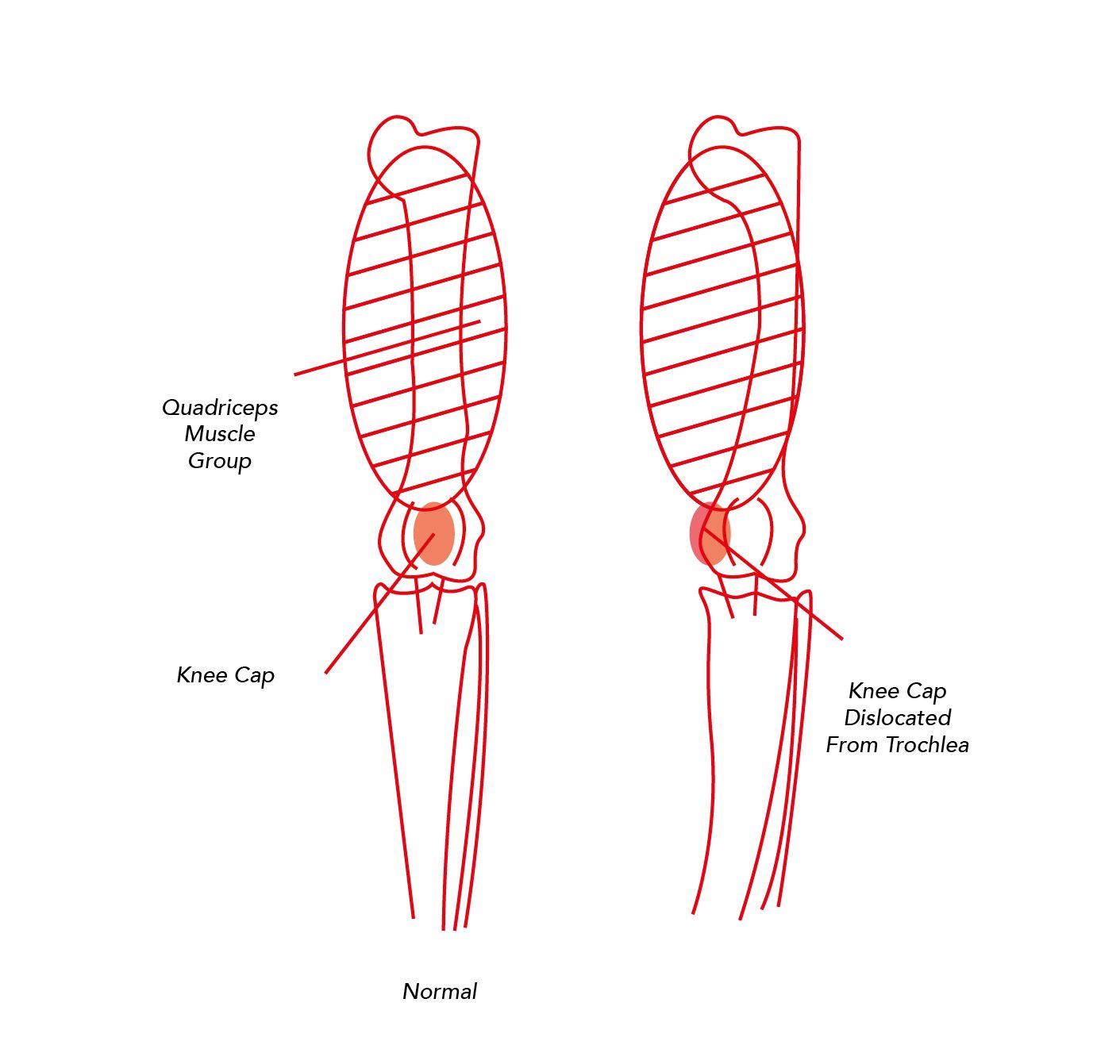

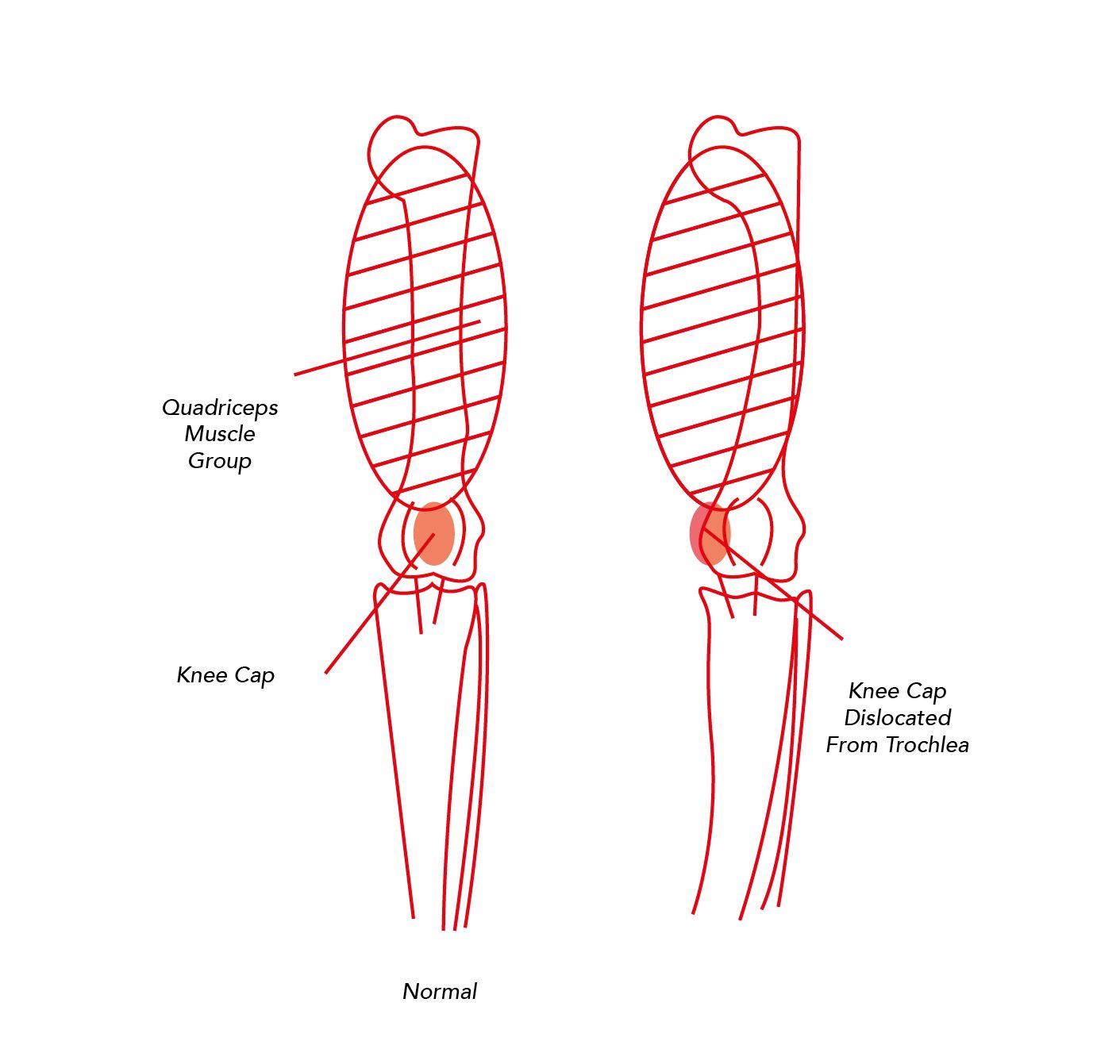

The knee cap dislocates due to a misalignment of the quadriceps, knee cap, trochlea and shin bone. Rather than pull the knee cap within the groove as it should, the quadriceps pull it out of the groove.

As the dog grows this misalignment causes the thigh bone and shin bone to become abnormally curved which makes the dislocation worse. As a result symptoms frequently worsen as the dog grows.

Despite extensive research thoug the exact cause remains unknown. However, certain breeds are predisposed to the condition it does suggest a likely genetic cause.

The basis of diagnosis is a thorough physical examination. Affected legs often have less muscle when compared to the normal leg. Manipulation of the joint may reveal instability of the knee cap and it is sometimes possible to move it in and out of the groove.

A luxating knee cap is often detected at routine physical examination of dogs which the owners have noticed no lameness.

Patellar luxation is graded from 1-4 (grade 4 is the most severe). A grade 4 luxation will sometimes only be diagnosed by x-rays.

Some dogs with a dislocating knee cap may be managed without surgery. These will usually be toy breeds with a grade 1 luxation and no overt lameness.

It should be remembered though that patellar luxation is a progressive condition and may worsen as the dog gets older – many dogs will benefit from surgery including those that have not yet developed any clinical lameness.

The aim of surgery is to stabilise the knee cap within the groove – this eliminates the skipping type of lameness seen, and also helps slow the progression of arthritis associated with cartilage destruction. Studies have shown that once the knee cap cartilage is destroyed the success of surgery is reduced by 50% – if we can operate before this happens the outcome for the dog is much improved.

There are three main steps that may be used in the surgical management of a dislocating knee cap.

1/ Groove deepening.

In cases where the groove is deemed too shallow it can be deepened by removing the groove’s cartilage, making the groove deeper and then replacing the cartilage. This creates a better seat for the kneecap to sit in.

2/Quadriceps realignment

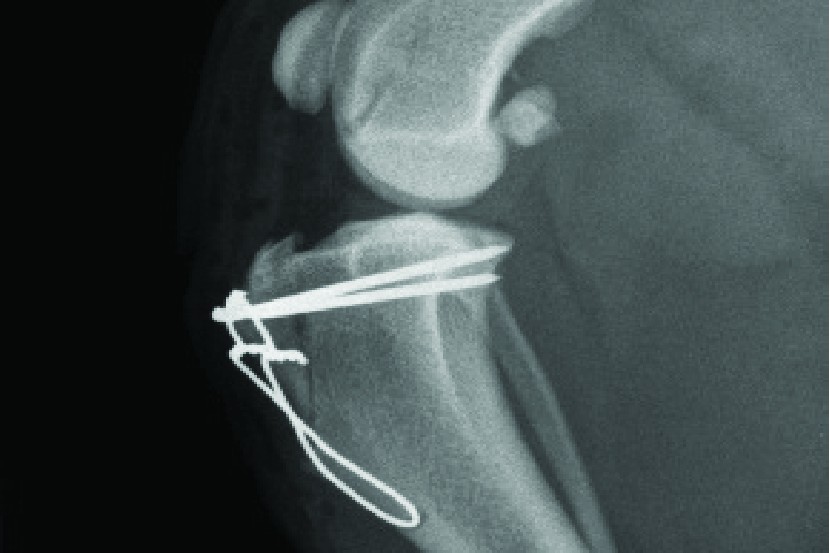

The knee cap attaches to the shin bone at a point called the tibial tuberosity. By removing this from the shin bone it can be repositioned to align the knee cap and quadriceps with the trochlea groove. It is then reattached in its new position using bone pins.

3/Soft tissue adjustment

In this procedure the soft tissues (muscle / ligaments) on either side of the knee are adjusted to increase / release tension on the knee cap to help it sit within the groove.

The outlook following surgery is generally good. Surgical intervention before the knee cap’s cartilage has been destroyed is a key factor – therefore surgery at first detection of knee cap dislocation and before the dog is actually lame is often advised.

Despite our best efforts some dogs will go on to develop joint stiffness and arthritis in later life.

Implant failure – In the immediate post-op period uncontrolled exercise can cause the bone pins to break. This can be minimised by following your post-op instructions.

Infection – all operations can lead to infection, this is increased when metal implants are used.

Under / over correction of the problem – it is possible for the knee cap to still dislocate despite surgery.

Fortunately at CCKC these complications are very rare.

The patella (knee cap) is a thick, circular bone which articulates with the femur (thigh bone) forming part of the knee joint. It covers and protects the front of the knee joint moving up and down a trochlea (groove) in the thigh bone.

The knee cap and groove are both covered in cartilage allowing smooth, friction free and pain less movement of the two bones.

The knee joint is designed so that the knee cap moves within the groove. The cartilage covering the back of the knee cap and groove allows smooth, pain free movement of the two against each other. When the knee cap moves outside of the groove it repositions onto bone and the knee no longer moves in the correct way. This bone acts as an abrasive against the knee cap cartilage grinding it off. The end result of this process is that bone in the knee cap is exposed causing increased inflammation and pain.

Most symptomatic dogs fall in to two different categories

1/ Young dogs who skip – these are often small terrier type dogs that hold their leg up for a few paces before putting it back down. Often they will kick the affected limb out. In these cases the knee cap is dislocating and getting stuck, and as a result they cannot bend their knee joint properly.

2/ Older dogs who have generalised stiffness and lameness. Often their knee caps have always been dislocated and as a result the knee cap has worn away causing severe arthritis. The knee joint can seem markedly thickened and the dog has difficulty climbing stairs, jumping into the car and completing walks.

The knee cap dislocates due to a misalignment of the quadriceps, knee cap, trochlea and shin bone. Rather than pull the knee cap within the groove as it should, the quadriceps pull it out of the groove.

As the dog grows this misalignment causes the thigh bone and shin bone to become abnormally curved which makes the dislocation worse. As a result symptoms frequently worsen as the dog grows.

Despite extensive research though the exact cause remains unknown. However, certain breeds are predisposed to the condition it does suggest a likely genetic cause.

The basis of diagnosis is a thorough physical examination. Affected legs often have less muscle when compared to the normal leg. Manipulation of the joint may reveal instability of the knee cap and it is sometimes possible to move it in and out of the groove.

A luxating knee cap is often detected at routine physical examination of dogs which the owners have noticed no lameness.

Patellar luxation is graded from 1-4 (grade 4 is the most severe). A grade 4 luxation will sometimes only be diagnosed by x-rays.

Some dogs with a dislocating knee cap may be managed without surgery. These will usually be toy breeds with a grade 1 luxation and no overt lameness.

It should be remembered though that patellar luxation is a progressive condition and may worsen as the dog gets older – many dogs will benefit from surgery including those that have not yet developed any clinical lameness.

The aim of surgery is to stabilise the knee cap within the groove – this eliminates the skipping type of lameness seen, and also helps slow the progression of arthritis associated with cartilage destruction. Studies have shown that once the knee cap cartilage is destroyed the success of surgery is reduced by 50% – if we can operate before this happens the outcome for the dog is much improved.

There are three main steps that may be used in the surgical management of a dislocating knee cap.

1/ Groove deepening.

In cases where the groove is deemed too shallow it can be deepened by removing the groove’s cartilage, making the groove deeper and then replacing the cartilage. This creates a better seat for the kneecap to sit in.

2/Quadriceps realignment

The knee cap attaches to the shin bone at a point called the tibial tuberosity. By removing this from the shin bone it can be repositioned to align the knee cap and quadriceps with the trochlea groove. It is then reattached in its new position using bone pins.

3/Soft tissue adjustment

In this procedure the soft tissues (muscle / ligaments) on either side of the knee are adjusted to increase / release tension on the knee cap to help it sit within the groove.

The outlook following surgery is generally good. Surgical intervention before the knee cap’s cartilage has been destroyed is a key factor – therefore surgery at first detection of knee cap dislocation and before the dog is actually lame is often advised.

Despite our best efforts some dogs will go on to develop joint stiffness and arthritis in later life.

Implant failure – In the immediate post-op period uncontrolled exercise can cause the bone pins to break. This can be minimised by following your post-op instructions.

Infection – all operations can lead to infection, this is increased when metal implants are used.

Under / over correction of the problem – it is possible for the knee cap to still dislocate despite surgery.

Fortunately at CCKC these complications are very rare.